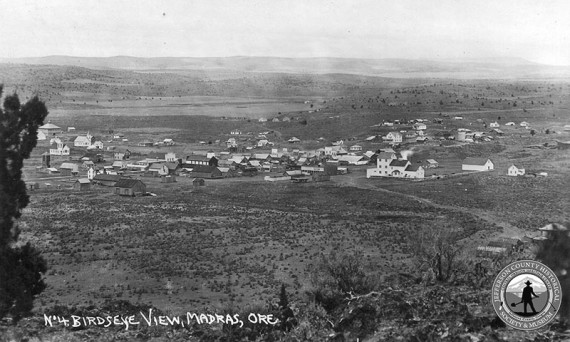

Birds Eye view Madras 1918.

In truth, although my father became a successful stockman who knew his herd by heart and was always in control of it, and my brother grew up as an expert horseman, I was no cowboy and I knew it. I was on reasonably good terms with our horses, Flicka, Dolly, Blue, Traveler, and Sky, but to me riding generally meant hard work and long hours, divided about equally between boredom and fear. None of my best friends were cowboys, either. I saw sure-footed Flicka slip and fall on my brother and break his leg as they were chasing a cow on the highway; I saw my father’s tall horse Traveler step in a badger hole at full gallop during a roundup and cartwheel on and over him, breaking his leg in thirteen places. I had my own share of minor horseback accidents and decided early on that, for thrills, I’d stick to machines. On my twelfth birthday, in place of the young horse I should have wanted, my folks conceded and gave me a motor scooter.

The only times I truly relished my periodic service as a reluctant cowpoke were when we were trailing the Box-Dot herd around the town of Madras, or even through it. Then the boredom and tensions of the job were offset by the prospect of being seen and wondered at by townspeople and schoolmates, as we nudged the critters down side-streets and vacant lots. Then, full of the romance of it all, I sat very tall in the saddle. Once when I was about thirteen, I nearly ran down a man and his son on the sidewalk in front of the Post Office, as my horse scrambled to bring a steer back into line. Far from being upset, the man told his little boy, “Look closely there, son, you’re seeing a little bit of the real Old West!” And over my shoulder, insufferably, I said, “That’s right, son.”

–from Jarold Ramsey’s NEW ERA: REFLECTIONS ON THE HUMAN AND NATURAL HISTORY OF CENTRAL OREGON, 2003.